‘Happiness Matters, Even in a Steady State Economy! Part 1: Sustainable Hedonism’ – Steady State Herald

This post was originally published on the Steady State Herald blog, 23rd February 2023.

Thriving is possible in a steady state economy (Lelkes)

From a historical perspective, we should be living in the happiest of all worlds. Ours is a culture ostensibly centered around happiness: The mainstream neoclassical economic system aims to maximize pleasure (utility) for all, and is based on the assumption that we humans seek the greatest pleasure and the least pain, and that this quest is the main driver of our actions.

Happiness has also been a philosophical, political, and personal striving for centuries. In the American Declaration of Independence, the “Pursuit of Happiness” is named as an unalienable right of humans, next to life and liberty. And today, the science of happiness is booming. On a personal level, the science of positive psychology offers a large range of tools that can support us in cultivating a joyful and meaningful life.

Happiness is relevant to steady state economies even though they do not focus on wellbeing as such. The quest for happiness, joy, and pleasure is an elemental life force. Who would not want to be happy? To create a profound systemic transformation, a positive, forward-looking narrative is essential to inspire and motivate individual and collective action, and this narrative would ideally offer some sense of happiness.

Many fear that shifting to a “green lifestyle” or reducing material consumption will bring a decline in wellbeing. I argue that it may be the other way round, that simplicity can advance happiness. But for this, we need to adjust our notion of happiness as well as our strategies for pursuing it.

In my recent book, “Sustainable Hedonism. A Thriving Life That Does Not Cost the Earth” (Bristol University Press, 2021), I challenge the current practice of hedonism, and I outline two alternatives—“sustainable hedonism,” and “flourishing life”—that do not harm others and the planet. This post explains sustainable hedonism, and next week’s installment extends the argument to the broader concept of happiness as flourishing life.

Economics and the Culture of Radical Hedonism

A key question surrounding happiness is what role pleasure plays in it. Mainstream economics assumes that self-interested pleasure-seeking ultimately drives action. It does not question what generates human tastes or desires, the values that underlie those desires, or the ethical consequences thereof. Moreover, built into neoclassical economics models is the assumption that people know what is best for them; they act rationally and are fully informed.

Even though behavioral economists like David Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Dan Ariely and others have shown that people tend to be predictably irrational and biased, and often do not know what is good for them, this knowledge has not been integrated into mainstream, neoclassical economics. This is not simply a scientific matter; its implications do not remain within the walls of universities and research institutes. This view of human nature affects our institutions and our culture as well.

Our mainstream culture rarely challenges our wants, our tastes, or our strategies for seeking pleasure and a good life, seemingly out of respect for individual freedom. Meanwhile, whole industries such as advertising and social media aim to alter our behaviour, urging us to seek pleasure by consuming their products or services. Social media and gadgets may be deliberately devised to create addictive attachment. Given their power and reach, our freedom is arguably largely an illusion.

Avoid the Extremes

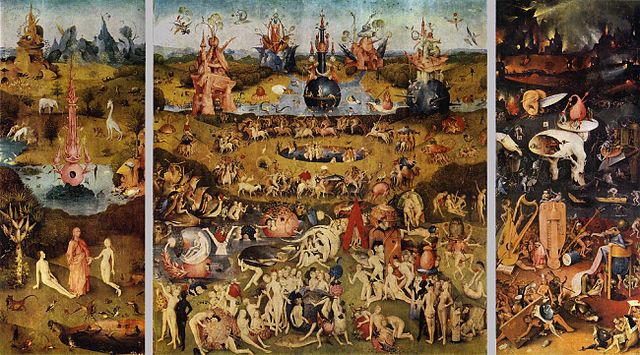

Our contemporary culture of hedonism has moved far away from its ancient roots. In its extreme form, known as radical hedonism, desires are unquestioned and pleasure is the ultimate yardstick of all striving. All things are evaluated simply as objects of desire and their appeal is based on whether they bring pleasure or not. Friendship and virtues such as honesty, love, and respect have no inherent value. People and nature matter only to the extent that they please us in the way we want to be pleased. All is centered around oneself in an egoistic and short-term manner.

Our current economic system, centered around growth, likely reinforces radical hedonism because consumption is cherished as a driver of a higher GDP, and vice versa. The more consumption, the better, this view holds, disregarding the quality and nature of the consumption and its consequences for people and planet. Our current system encourages us to seek pleasure, to satisfy our longing with material consumption: essentially, it says “we can buy happiness.” In short, happiness is often reduced to pleasure or a short-lived spell of positive emotion.

On a personal level, radical hedonism is likely to lead to addiction, overconsumption, alienation, mental and physical imbalance, and suffering. On a collective level, it creates a culture of materialism and an overuse of resources beyond planetary limits.

What is the alternative to destructive radical hedonism? What mindset can help us create a better world that supports human thriving as well as the regeneration of damaged ecosystems?

Sustainable Hedonism: Pleasure With Inner Freedom

Greek hedonist philosophers held that humans are ultimately driven to seek pleasure and avoid pain, including physical and mental pleasures and pains. They devoted their philosophies as well as their personal lives to exploring how to enjoy life to the fullest and how to suffer the least. They realized that immense suffering can arise from longing for things we cannot have, so they called for critical scrutiny of our inclinations. They warned that we should not become slaves of our desires.

Epicure, for example, warned that it is better to “avoid fairs” to prevent longing for things we do not really need. Vain and empty desires do not serve our wellbeing, he advised. Today, avoiding fairs could mean refraining from passing time in shopping malls, watching commercials, or online shopping as a way to release stress. This ancient wisdom is confirmed by ample evidence from modern psychology as well: unrestrained pleasure-seeking strategies do not bring high levels of wellbeing and may lead to addiction. On the other hand, we can develop our abilities to lead a joyful life.

I call this conscious approach to pleasure “sustainable hedonism”—the refined enjoyment of life with awareness, self-reflection and an inner independence. It is clearly different from today’s negative understanding of hedonism: the egoistic, destructive practice of radical hedonism described earlier.

Sustainable hedonism offers higher personal and social wellbeing, and a much-needed alternative strategy for pursuing pleasure and joy in life. It is sustainable in the sense that it can be sustained on a personal level (without harmful effects on health and wellbeing) and on a collective level (as it respects our planetary boundaries, ecological balance, and social fairness).

What the Ancients Can Teach Us

The ancient hedonist philosophers can yet inspire us: they advocated slowing down to savour the moment, learning to use all our senses, and enjoying and appreciating to the fullest the things we already have. Or we can learn from Aristotle, who, while not a hedonist philosopher, advocated self-mastery, where desires do not own us, but where instead we have control over them. Self-mastery is different from self-denial, as the latter may be hurtful.

Today we might say that self-mastery is a conscious minimalism whereby one takes a critical stance in the face of the seduction of consumerism, of status goods, and of fashion hypes. It gives us autonomy over our wallets and the objects of our attention, as well as the ability to critically assess what we really need. Sustainable hedonism is a practice of inner freedom, reclaiming our autonomy and power. Empirical evidence from contemporary psychology suggests that conscious green adjustment of lifestyles, and participation in the solidarity economy—practices that fit comfortably in a lifestyle of sustainable hedonism—are likely to increase wellbeing.

Our search for pleasure is a fundamental element of our vitality, of our life force. It follows that the steady state economy, if it is to be politically feasible, cannot be an ascetic ideal of self-denial, lacking in pleasure or joy. Rather, it could encourage us to explore the right approach to pleasure and pleasure-seeking. It would help us question our tastes and preferences, to consciously and deliberately reflect on our desires.

Sustainable hedonism is an invitation for such conscious adjustment, based on Greek philosophy as well as modern psychology. The realignment of our ways of seeking pleasure and satisfaction is likely to benefit society, in terms of ecological balance, as well as ourselves, in terms of mental and physical health. However, we would be mistaken to restrict our definition of happiness to pleasure-seeking. In next week’s Herald, I’ll explore the broader topic of happiness and how to achieve it.